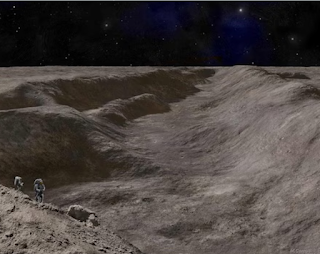

The recent discovery of two massive canyons on the Moon’s far side has taken the scientific community by surprise, providing new insights into the dynamic and violent history of asteroid impacts on the Moon. This discovery, led by scientists from the Lunar and Planetary Institute (LPI), reveals features that rival the size and depth of Earth’s iconic Grand Canyon, offering a fascinating glimpse into the catastrophic events that took place on the Moon during the early stages of the solar system's formation.

The Grand Canyon, one of the most famous geological formations on Earth, measures 29 kilometers in width and reaches depths of more than 1.8 kilometers. The two canyons found on the Moon share a similar scale, adding an exciting dimension to our understanding of lunar topography. These canyons, named Vallis Planck and Vallis Schrödinger, are located on the lunar far side, an area that is often shielded from direct observation from Earth. This makes their discovery all the more significant, as it provides further evidence of the Moon's violent and ever-changing landscape.

The study, which was published in the prestigious journal Nature Communications, provides groundbreaking details about the formation of these canyons. The scientists believe these structures were formed during a period of intense planetary bombardment, when both the Earth and the Moon were being resurfaced by the impacts of asteroids and comets. According to David Kring, the lead author of the study, the Moon was struck by an asteroid or comet that traveled over the lunar south pole. As the object brushed past the mountain summits of Malapert and Mouton, it slammed into the lunar surface, releasing an incredible amount of energy. This impact caused the violent ejection of debris, which then carved two deep and wide canyons, each comparable in size to Earth's Grand Canyon. Remarkably, this monumental process occurred in less than 10 minutes, in stark contrast to the millions of years it took for Earth’s Grand Canyon to form.

The scientists used data obtained from NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter spacecraft to map out these enormous canyons. They then employed advanced computer modeling techniques to simulate the behavior of the debris ejected by the asteroid or comet impact. The results were nothing short of astonishing—debris from the impact was ejected at speeds of up to 3,600 kilometers per hour, a velocity that enabled it to travel vast distances before landing back on the lunar surface, contributing to the formation of the canyons.

Vallis Planck, the longer of the two canyons, spans a length of about 174 miles (280 kilometers) and has a depth of 2.2 miles (3.5 kilometers). Vallis Schrödinger, the second canyon, extends for 168 miles (270 kilometers) and reaches a depth of 1.7 miles (2.7 kilometers). These dimensions highlight the sheer scale of the forces involved in the Moon's past impacts. The canyons are not random or irregular formations; they are striking, straight-line scars that radiate outward from large, round impact craters that were created by the initial asteroid or comet strike.

Interestingly, smaller craters can also be found surrounding these canyons, marking the locations of unrelated impacts. This indicates that the Moon has been subjected to continued bombardment over millennia, further emphasizing the chaotic nature of the early solar system. Despite these continued impacts, the two giant canyons remain the most dramatic evidence of the catastrophic collisions that once ravaged the Moon's surface.

The asteroid or comet responsible for the creation of these canyons is thought to have been approximately 25 kilometers in diameter. This is substantially larger than the asteroid that struck Earth around 66 million years ago, an event that led to the extinction of the dinosaurs. In terms of the energy released by the impact, it is estimated that the event unleashed an energy equivalent to 130 times the total global inventory of nuclear weapons. This makes the lunar canyons one of the most impressive geological features in the solar system, considering the enormous force required to form them.

The object that struck the Moon likely hit at a speed of approximately 55,000 kilometers per hour. Upon impact, the debris ejected at an extraordinary velocity of around 1 kilometer per second (approximately 3,600 kilometers per hour). This high-speed debris created secondary impact craters, which in turn, helped carve out the grand canyons. These findings also shed light on the process of planetary resurfacing that occurred during a period when the Moon was bombarded by numerous large asteroids and comets, marking a time of intense geological activity.

The formation of the lunar canyons likely occurred during what scientists refer to as the Late Heavy Bombardment period, a time when both the Earth and the Moon were frequently struck by large celestial objects. This period of intense impacts would have had a profound impact on the Moon’s geological evolution, influencing the development of its surface features and ultimately shaping the Moon we see today. The discovery of these canyons provides valuable information about the nature of these impacts and how they influenced the lunar environment.

One of the most striking aspects of this discovery is the scale of the energy involved. The formation of these canyons represents one of the most extreme examples of planetary-scale forces in our solar system. The magnitude of energy required to carve such large-scale features on the Moon is mind-boggling, highlighting the power of these ancient asteroid and comet impacts.

This discovery is likely to have significant implications for our understanding of the history of the Moon and the dynamics of the early solar system. It offers new insights into the kinds of processes that shaped the Moon’s surface, as well as the nature of the asteroid and comet impacts that played a key role in the lunar evolution. As scientists continue to study these canyons and their formation, they hope to uncover more information about the history of the Moon and its interactions with other bodies in the solar system.

In conclusion, the discovery of the two massive canyons on the Moon provides a fascinating glimpse into the Moon's violent and dynamic past. It also serves as a reminder of the powerful forces at play in the early solar system, when asteroid and comet impacts reshaped the surfaces of the planets and moons. As scientists continue to study these lunar features, they hope to learn more about the processes that have shaped our nearest celestial neighbor and further our understanding of the solar system's complex history.